- Home

- Suzanne Selfors

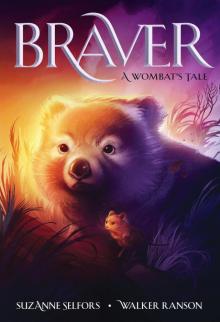

Braver

Braver Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Authors

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

St. Martin’s Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on Suzanne Selfors, click here.

For email updates on Walker Ranson, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Dedicated to Brian Jacques, whose stories we will always treasure and without whom we never would have started writing.

1

PEACE AND QUIET

“Lola, please stop asking so many questions.” Arthur Budge, a dark-brown wombat, pulled a parsley sprig from the ground, then frowned at his daughter. “You’re giving me indigestion.”

“But—”

“Questions can wait,” he said. “We have all the time in the world.”

Alice Budge, a light-brown wombat, handed Lola a clump of freshly dug snow grass and whispered, “Do try to have patience. You know how much your father enjoys the peace and quiet.”

Lola sighed. She sat next to her father, close enough that she could smell the parsley’s sharp notes as he bit through its stem. Despite his reprimand, Lola didn’t want to stop asking questions. On this night she’d already asked thirteen, from “Why do our teeth keep growing?” to “Why are our rumps so hard?” But the answers were often some variation of “Because that’s just the way it is.” Or “Because that’s how it’s always been done.” Lola flicked a worm from the snow grass clump, then sank her teeth into the succulent green blades.

It was a lovely night in Tassie Island’s Northern Forest. Lola and her parents were foraging in their favorite clearing, where wild grasses and herbs grew in abundance. Every wombat family kept a tidy garden patch next to its burrow, growing radishes, tomatoes, and lettuce for meals, but foraging was good exercise and provided “important nutrients,” as Alice often said. Lola chewed and looked up. A new moon shone through giant gum trees that seemed to reach as high as the distant mountains. No songs drifted down, for the birds were all in bed. Except for the wombat family’s quiet chewing sounds, the forest was swaddled in silence.

Silence.

There were few things more valued among the bare-nosed wombats of the Northern Forest. Singing and whistling were frowned upon, except on the queen’s birthday. Reading, with its soft sounds of page turning, was the favored hobby. Wood carving, with its delicate sounds of chipping, was the vocation of choice. If quiet had been something tradable, like bowls or spoons, wombats would have hoarded it with dragon-like avarice.

Except for Lola, who knew she was a bit of an oddball because she loved talking. And she loved telling stories to the forest mice. But storytelling had to be done while her parents slept, for they would be ashamed if they discovered their daughter’s unwombat-like activities.

With the grass eaten, Lola wandered over to a log and started munching on some moss. It was one of her favorite flavors of green and quite the thirst quencher. But though she was enjoying the meal, she sighed loudly. It was proving to be another quiet night, following another quiet day in her, as ever, quiet life. This sameness never seemed to bother her mother or father. Arthur and Alice relished the predictability of their wombat existence, but Lola was always on the lookout for someone to talk to and if she found someone, be it a bird or a mouse, she talked. At length. Maybe that was why Lola’s parents looked more haggard than other wombat parents, and why her father’s stomach was prone to episodes of upset. Parsley, known for its stomach-settling qualities, was his herb of choice.

“What’s that?” Lola dropped her pawful of moss, scrambled atop the log, and peered down at the stream. First came the squelch of steps along the muddy bank. Then she caught sight of a dark shape that was clearly wombatish in nature. “Hellooo!” Lola called.

Arthur gasped. “Lola, no, not again.”

“It’s our neighbor, Mister Squat. I’m being friendly. Don’t you want me to be friendly? Hello! Hello!” Lola stretched her short arm as far as she could in a wave, hoping to get the old wombat’s attention.

It worked. He stopped in his tracks, then glanced up at the log through his thick spectacles.

“Mister Squat! It’s me, Lola! Lola Budge! Are you having a nice night of foraging? Did you find some watercress?”

Mister Squat grumbled something under his breath and turned around so his prodigious rump blocked Lola’s view. Then he began digging in the streambed for roots.

“Maybe he didn’t hear me.” Lola took a deep breath, cupped her paws around her mouth, and bellowed, “MISTER SQUAAAAAT!” His fur bristled and his ears scrunched up in sudden displeasure.

“Oh, hooly dooly.” Alice hurried to Lola’s side and clamped a paw over Lola’s mouth, her own ears partially clamped shut as well. “Please stop hollering. You’ll wake the daytimers.”

Lola squirmed free. “But Mum,” she pleaded. “I’m just trying to be neighborly.”

Alice shook her head in a worried way, which she tended to do around her only joey. “Sweetie, how many times must I remind you that talking to our neighbor without invitation is bad manners?”

“Yes, I know,” Lola grumbled. “I’m disturbing his ‘peace and quiet.’”

“Why isn’t she shy like the rest of us?” Arthur asked his wife.

“Because she isn’t,” was Alice’s answer—the same answer she gave each time he asked that question.

Lola chewed another mouthful of moss, her gaze fixed on Mister Squat, who shone silver in the moonlight. As he sat, feasting upon a root he’d pulled from the mud, Lola’s mind filled with questions. How old was he? Could he see without his spectacles? Did he like carving spoons and bowls? She certainly didn’t.

As Lola flicked a piece of moss from her white whiskers, Mister Squat stopped eating, turned around quickly, and faced the stream. He adjusted his spectacles. He shook his head. He shrugged. He shook his head again. Lola took a quick breath. Wait. What was happening? Was something happening?

She scrambled along the log, trying to get a better view. Mister Squat was clearly looking at something in the distance. He shrugged again. Lola could barely contain her excitement. She reached the end of the log and stood on the tips of her toes, her long claws prickling the bark. Why was he shrugging? Was he talking to someone? Yes, he was talking to someone. But Mister Squat never talked to anyone. She’d never heard his voice.

But then he turned abruptly, abandoned the root, and hurried up the trail that led back to the burrows.

She wanted to call after him but wrinkled her nose, remembering her mother’s words. Bad manners? Lola narrowed her eyes. No one else thought it was bad manners to say goodbye. Why did wombats have to be so antisocial? The only time the community got together was on Queen Myra’s birthday, to feast and sing songs in her honor. Though Lola had never met the queen, she’d been raised to love and admire her, as had all the wombats of the Northern Forest. Queen Myra’s birthday was considered the most important day of the year. But during the rest of the year, there was no need for group gatherings. The wombats let each other know that all was well by displaying their cubic droppings on rocks. While out foraging, Lola’s mom might say, “Oh look, there’s Mister Pudge’s dropping. He appears to be doing just fine.” Or, “Oh look, t

here’s Missus Portly’s dropping. She seems healthier than ever.”

Lola was aching to find out who Mister Squat had been talking to. She slid off the log. “May I—”

A sharp look and gnashing of teeth from her father answered the question.

With Mister Squat gone and nothing interesting to watch, Lola finished her moss. Then she patted her belly rhythmically with her hind paw—a wombat sign that the meal had been satisfying and that the belly was contentedly full. Arthur and Alice also patted their bellies. Then the Budge family began to waddle along the forest path, climbing over fallen branches and ducking beneath tangled vines. But Lola had one more question on her mind, and it was one of the best questions she’d ever thought of, so it was worth risking another reprimand.

“Mum, Dad, if you were both shy, how did you meet?” Lola made sure that her voice was very hushed when she asked the question. But if her father didn’t answer, she was prepared to ask it again. And again.

To her surprise, he chuckled. “We grew up a few burrows apart. I was impressed because your mum’s droppings were always perfect cubes.”

“Thank you, my dear.”

“You’re welcome. Of course, I was too shy to talk to her, so I left her a letter. And she wrote back. After thirteen letters, I finally worked up the courage to forage with her.”

This was the most talking her father had done in weeks and it was thrilling. Lola was about to ask another question, but a serious look from her mother reminded her not to push things.

Upon reaching the burrow, Arthur opened the door. Then Lola and her parents waddled downward, following a tunnel beneath the roots of a celery-top pine until it branched into a series of rooms. Each room had been dug by paw, then fortified with wooden beams. Skylights were set into the tops of the rooms, allowing moonlight to trickle in. Though Lola and her parents could see well in the dark, this extra light was helpful for activities such as reading and carving. And during the day, when they slept, curtains were drawn across the skylights to block the sun.

The largest room was their main living area. It had a river-stone table to carve upon, circled by three chairs. Specialty carving tools, such as chisels and gouges, hung from a tool rack. Wall shelves held some of the lovely bowls that Arthur and Alice had made. A broom stood in the corner, for sweeping up wood chips. But the central focus of the room was the looming grandfather clock. Carved by Arthur’s father, it was a prized family heirloom and ticktocked with quiet perfection.

Two passageways split off from the main chamber. One led to a storeroom where the Budge family kept their winter food. The other led to the bedrooms, with their straw mattresses and moss-filled pillows. When she was much younger, Lola’s parents often had to replace the moss in Lola’s pillow because of Lola’s midday snacking. Wardrobes contained extra blankets, needed during the deep freeze of winter, and traveling cloaks, though Lola’s was unused, as she’d yet to travel anywhere. All in all it was a tidy and simple dwelling.

“Lola, are you going to work on your bowl?” Arthur asked. He picked up a piece of soft pine and began to hollow it. As he worked he would alternate using claws, chisels, and even his teeth.

“No, thank you,” she replied. “You know I don’t like carving.”

“How will you buy the essentials of life if you don’t have anything to trade in return? Woven fabrics and glass panes are expensive and have to be shipped from Dore.” Arthur shook his head sadly. “Plus, you need to wear out your teeth somehow. You don’t want to end up with them sticking in the ground like that Biggun Longtooth from the old stories, do you?”

Lola picked up her bowl and began gnawing at it, oozing boredom.

“Maybe she will be good at something else,” Alice said hopefully.

“But what could that be? She’s a wombat, and wombats carve.”

“I’m good at talking,” Lola almost said, but she knew a statement like that would bring a frown to her father’s furry face.

While Arthur and Alice sat at the table and worked on their bowls, Lola tossed hers aside and tucked herself into the corner to read her favorite book, The Tales of Tassie Island, though perhaps she would skip over Longtooth’s story today. Each story began in the same way: “Gather ye round and prick your ears, for a tale is about to be told.” She knew all the stories by heart, but that didn’t matter. How she loved the thrilling high-sea adventure of “The Penguin Pirates” and the heartbreaking romance of “The Quoll Princess and the Beast.” Each story was usually a quick read, but on this night Lola was having trouble concentrating, her whiskers twitching uncontrollably. She couldn’t stop thinking about Mister Squat. He’d ignored her hellos, but he’d obviously talked to someone else. Who had been able to get Mister Squat’s attention? And why? She’d only finished two paragraphs when her mother patted her on the head. “The sun is rising.”

Lola kissed her parents on their furry cheeks, then shuffled to her room and climbed into her bed for the day’s sleep. Alice and Arthur retired to their own room and soon, the sounds of their deep breathing filled the burrow. Lola closed her eyes. She curled on her left side. Then curled on her right side. She rolled onto her back, opened her eyes, and stared at the dirt ceiling. The night’s events tapped at her mind like raindrops onto the ground.

Mister Squat never spoke to his wombat neighbors, so did that mean he’d encountered someone who wasn’t a neighbor? Someone who didn’t usually live in the burrows? Were there clues left behind? There was only one way to find out.

Lola slipped out of her bed and tiptoed from her room. She stopped outside her parents’ door, listening to make sure they were still in a deep sleep. Then, ever so quietly, Lola Budge made her way outside.

2

MESSAGE IN A BOTTLE

When Lola emerged from the burrow, she took great care to look around, her eyes blinking against the brightness. As she waddled on, her vision slowly adjusted. Even though she’d done this before, daylight always mesmerized her. The morning forest was covered in a small layer of water droplets that sparkled in the sunlight, much like the stars at night. The ruffled leaves of the tanglefoot trees blazed a brilliant dark green.

“G’day, Lola.” Lola paused and looked up. A forest mouse peered down from her little cottage, built into a hollow stump. “Sneaking out again, are ya?”

“Yes,” Lola whispered. If she woke the wombat neighbors, they’d surely complain to her parents and she’d get in trouble for wandering outside the burrow, no matter what her reason.

“Gonna tell us a story?” a young mouse asked, sticking his head out of the nest. “How about the one where the pelican turns into a glossy ibis. What’s that one called?”

“‘The Ugly Hatchling,’” Lola replied.

“We love that story, we do. Tell us that story.” The mice sat on the edge of their porch, kicking their feet as they eagerly awaited their morning entertainment.

It was a lovely request, and normally Lola would be thrilled to indulge. “I’d like to, but I’ve got something to do,” she told them.

“Well, don’t you go mucking about for too long,” the mama mouse advised with a wink. “Your mum and dad will throw a wobbly, they will, if they find ya gone again. Just like I would if mine was to sneak out.” Her eyes shifted to look down at her youngster with a heavily raised eyebrow.

“I’ll be quick,” Lola assured them. Then she made her way down to the stream, following the path that had been worn into the forest floor over the years by dozens of wombat paws. Things looked so different in sunlight. The water glistened and shone, allowing Lola to see the smooth rocks below and the thin silver fish that darted about. She’d always loved this stream. She and her parents had waded through it many times, crossing to the other side where the watercress grew thick. Lola had asked her mother where the stream went and she’d said it emptied into the Fairwater River. But a rushing river was too dangerous for wombats, so Lola always swam in the quiet pools of the stream.

Lola found the exact spot where Mi

ster Squat had been sitting, his paw imprints still visible on the muddy bank. She looked up and down, but there were no other paw prints that might reveal what sort of critter he’d been talking to. Maybe he’d been talking to himself? Lola did that sometimes.

She sighed. Even though the mystery had not been solved, perhaps the morning wasn’t a total loss. She could return to the hollow stump and tell the mice a story. Then she could hurry back to her burrow with plenty of time to sleep the rest of the day away, her parents none the wiser. That seemed a good plan. But when she turned to head up the path, a splash drew her attention. On the other side of the stream, a dark shape was swimming in one of the deep pools. It couldn’t be a wombat because all the other wombats were still tucked into their burrows. She guessed it was a forest rat but noticed that the tail was wide and paddle-shaped. The critter swam in a circle, then disappeared underwater. Lola’s whiskers bristled with curiosity. She had to find out what it was.

She splashed across the stream, her claws gripping the slippery rocks, then plopped herself onto a boulder at the edge of the pool. How could the critter stay underwater for so long? “Hellooo!” She reached one paw into the pool and waved underwater.

“Oi! Stop doin’ that!”

The critter had popped out of the water. A pair of swimming goggles covered his eyes and he had a funny flat bill instead of a nose. He pushed the goggles up his forehead and glared at her with his tiny black eyes. Lola found herself looking at a small, irate platypus.

“Stop doing what?” she asked.

“Stop churnin’ up the water! How’m I gonna catch me brekkie if yer splashin’ about, interruptin’ me electroreception?”

Lola lifted her arm from the water. “Sorry.” She frowned. “What’s electro—?”

“Electroreception,” he said snippily. “Ya don’t know about electroreception?” She shook her head. “Well I don’t have time to explain it to ya ’cause I’m far too busy.” Lola wondered why he was so cranky. Maybe he was hungry. Lola watched as he dove again, somehow not disturbing the water. A few moments later, he emerged with a blue yabby in his mouth, which he quickly ate. Then he climbed out onto the rocks. With his webbed paws, he reached for a green bag that was slung around his body. That’s when Lola noticed the spur.

The Rain Dragon Rescue

The Rain Dragon Rescue Ginger Breadhouse and the Candy Fish Wish

Ginger Breadhouse and the Candy Fish Wish Ever After High: Lizzie Hearts and the Hedgehog’s Hexcellent Adventure: A Little Shuffle Story

Ever After High: Lizzie Hearts and the Hedgehog’s Hexcellent Adventure: A Little Shuffle Story The Griffin's Riddle

The Griffin's Riddle Smells Like Pirates

Smells Like Pirates Duchess Swan and the Next Top Bird

Duchess Swan and the Next Top Bird The Sasquatch Escape

The Sasquatch Escape Hopper Croakington II and the Princely Present

Hopper Croakington II and the Princely Present The Order of the Unicorn

The Order of the Unicorn A Semi-Charming Kind of Life

A Semi-Charming Kind of Life Braver

Braver Kiss and Spell

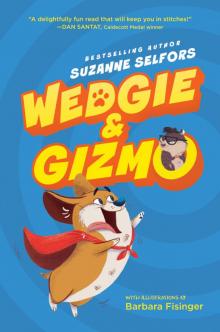

Kiss and Spell Wedgie & Gizmo

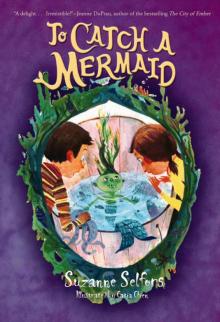

Wedgie & Gizmo To Catch a Mermaid

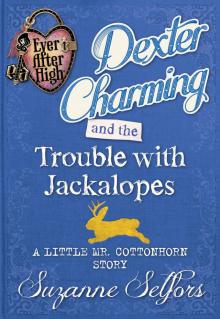

To Catch a Mermaid Dexter Charming and the Trouble with Jackalopes

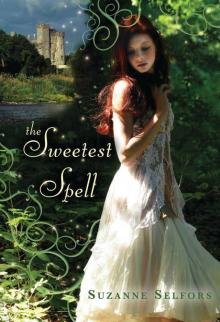

Dexter Charming and the Trouble with Jackalopes The Sweetest Spell

The Sweetest Spell CoffeeHouse Angel

CoffeeHouse Angel Wish Upon a Sleepover

Wish Upon a Sleepover Smells Like Dog

Smells Like Dog Ever After High

Ever After High Ever After High: A Semi-Charming Kind of Life

Ever After High: A Semi-Charming Kind of Life Saving Juliet

Saving Juliet Darling Charming and the Horse of a Different Color

Darling Charming and the Horse of a Different Color Wedgie & Gizmo vs. the Toof

Wedgie & Gizmo vs. the Toof Spirit Riding Free--The Adventure Begins

Spirit Riding Free--The Adventure Begins The Fairy Swarm

The Fairy Swarm Ever After High: Next Top Villain: A School Story

Ever After High: Next Top Villain: A School Story Fortune's Magic Farm

Fortune's Magic Farm The Lonely Lake Monster

The Lonely Lake Monster Spirit Riding Free--Lucky and the Mustangs of Miradero

Spirit Riding Free--Lucky and the Mustangs of Miradero Smells Like Treasure

Smells Like Treasure Mad Love

Mad Love