- Home

- Suzanne Selfors

Spirit Riding Free--Lucky and the Mustangs of Miradero Page 6

Spirit Riding Free--Lucky and the Mustangs of Miradero Read online

Page 6

Once again, Lucky’s team sat in silence. This turn of events was worrisome to Lucky. She was already in trouble thanks to her tardiness. And over the past few months she’d turned in some homework late—not out of laziness, but because there’d been so much she’d had to get used to in this new life. Chores, such as laundry, sweeping, and cooking, took a long time. She really wanted to do well on this group project. She wanted to show Miss Flores that she was a dedicated student. But if Pru and Maricela continued to act stubbornly, then they’d all fail!

Miss Flores clapped her hands. “Attention, everyone. I think you’ve had enough time to discuss. Now I’d like each group to tell us what they’ve decided to do.” She pointed around the room. Snips, Mary Pat, and Bianca said they wanted to make snow cones out of real snow. Because they were only six years old, Miss Flores thought that was an appropriate choice. Turo (who was a good friend to the PALs) and the older students were going to map the winter sky. Then Miss Flores turned to Lucky’s group. “We don’t know yet,” Lucky said. “Can we have more time to think about it?”

“Yes, but I’d like you to make a decision by Monday.”

Pru was scowling something fierce. As was Maricela.

“How are we going to get them to agree?” Abigail whispered to Lucky.

Lucky whispered back, “I’m the team captain, so I’ll figure it out. I moved across an entire continent and I learned how to ride a wild mustang. This will be a cinch.”

But would it?

12

Saturday was spent helping Pru at the Granger barn.

From the outside it looked like an everyday sort of barn, red with white trim, and with a large sliding door and a peaked roof. But the PALs had transformed the interior, painting the stalls yellow with pretty green trim, and hanging decorative signs to mark which stalls belonged to Boomerang, Chica Linda, and Spirit. Each horse had a window to peek out of, but Spirit’s stall was the only one that had a door, allowing him to come and go as he pleased. Sometimes he spent the night, sometimes he didn’t. There was no pattern with him. Lucky had accepted this fact, but as she and Abigail walked to the Granger Ramada, she couldn’t shake the worry over the fact that it had now been six days since she’d seen him.

And that’s why she squealed with glee when she found him waiting inside the barn. “Spirit!” She wrapped her arms around his neck. He greeted her with a soft nicker.

“I knew there was nothing to worry about,” Abigail said. She opened her lunch bag and took out an oatmeal cookie. Chica Linda delicately accepted her piece. Boomerang reached out with his teeth and grabbed his. Then he tried to grab the third piece. “No, Boomerang, this one’s for Spirit.” Spirit accepted the treat. “Horses sure love my oatmeal cookies.”

“We love them, too,” Pru said as she took one.

Lucky grabbed a brush and ran it down Spirit’s flank. Even though she never trimmed his forelock or mane, he sure loved being brushed. His neck relaxed as he slowly set his head forward and down, exhaling a deep, fluttering breath through his nostrils.

Pru’s father had left a note in the barn, next to three hammers, a jar of nails, and some boards. For patching the holes, the note read. After they’d brushed, watered, and fed their horses, the girls buttoned up their coats, wrapped scarves around their necks, and walked around the barn. They found three holes, each caused by rotting wood. They removed the old boards and replaced them with new ones. “What’s this?” Lucky asked, peeking under a tarp.

“Oh, I forgot all about that,” Pru said. “That’s an old sleigh. We used it when I was little. But we haven’t had a big snow in a while, so it’s been sitting there.”

Images flooded Lucky’s mind, of her family’s annual sleigh ride through the park. Of the red sleigh, the beautiful white horse, the sound of bells jingling. She remembered sitting next to her grandfather, a wool blanket over their laps, sipping hot cocoa as they glided over the snow-covered lawn. With all these memories, a pang of homesickness struck her, as it did now and then.

“Lucky, are you okay?” Abigail asked, looking into her eyes. “You look sad all of a sudden.”

“I’m okay. Just remembering winter back in Philadelphia. We took a sleigh ride every year.”

“Maybe we’ll get the chance to keep the tradition going,” Pru said.

Abigail nodded. “I sure hope so. I’d love to ride in this again.”

After patching the holes, the next chore was to clean the stalls. Not a pleasant job, but very necessary. It was important to keep the stalls tidy, not just for the horses, but to keep rats, mice, and other critters from nesting in them. They raked the soiled straw, dumped it into a wheelbarrow, and then scrubbed the floors. Lucky rolled up her sleeves and scrubbed the water trough. Pru cleaned out the food trough. When they’d finished the hard work, Abigail sat on a stool and made snowflakes from blank sheets of paper she’d torn from her notebook. Then they strung the snowflakes from the rafters. “It’s like a winter wonderland,” Lucky said. As the afternoon progressed, Lucky thought about bringing up the Maricela issue. They’d have to talk about the group project sooner than later, but she didn’t want to spoil the mood.

As it turned out, Maricela spoiled the mood all by herself.

“It stinks in here,” she announced as she barged into the barn, her wool hat pulled snugly around her face.

“If you don’t like the way it smells, then you’re free to leave,” Pru told her as she pushed the wheelbarrow outside.

“I’m here to talk to Lucky.” Maricela strode up to Lucky, who was sweeping cobwebs out of a corner. “I was wondering if you’d like to come over and have dinner with us tonight.”

Lucky swept around Maricela’s feet. “Thanks, Maricela, but I’m going to be working until late. We have to get the barn ready in case we get a lot of snow.”

“Can’t you have the servants do this?”

Pru, who’d returned with the empty wheelbarrow, glowered. “We don’t have servants, Maricela. We have employees. Besides, these are our horses and we want to take care of them.” Chica Linda snorted.

“I don’t know why you have to do so much horse stuff. They smell bad and they’re dumb.” Spirit didn’t seem to like Maricela’s nasty tone, because he stepped up to her and, with a bold look, neighed loudly. She squealed and backed away. “Oh, keep him away from me. He wants to bite me!”

“I don’t blame him,” Pru said. “You come in here and tell him that he stinks and that he’s stupid.”

Abigail finished hanging another snowflake and climbed down the stepladder. “If you just took the time to get to know them, you’d see that they’re really sweet.”

Spirit’s ears were pinned forward, his tail slightly lifted. He had never bitten anyone, except the mesteñeros who’d tied him up with ropes and had tried to saddle him. But in that situation, he’d been protecting himself. Lucky was pretty sure he wouldn’t bite Maricela, but he was staring at her with a look of pure annoyance. “Maricela,” she said, stepping between them. “We need to talk about our group project. Have you thought about Pru’s idea, that we study how animals survive in the winter?”

Maricela looked at Pru. Pru grabbed a shovel and began to walk past Maricela, but she tripped on something. A piece of manure landed right next to Maricela’s boot. “Disgusting!” Maricela jumped away. “If you’re not nicer to me, I’m never going to agree on our project!” And she stomped out the door.

Lucky and Abigail looked at Pru, who shrugged innocently. But when Lucky looked at the floor she didn’t see anything that might have tripped her.

“Wow, I haven’t seen Maricela that angry since that time Snips put a dead grasshopper in her sandwich,” Abigail said. “She ate half of it before she realized.”

Lucky followed Pru as she put away the wheelbarrow. “Pru,” she said, “we don’t have a choice. We have to work with her. Maybe it would be easier if we just did what she wants. The winter clothing thing is silly, but we could do it and get a good grade. And then

we wouldn’t have to keep fighting with her.”

“No.”

Lucky sighed. “I know you have this rivalry with Maricela, and I know she’s not very nice, but I’m worried about my grades. I don’t think Miss Flores likes me that much right now. I’ve been tardy and I’ve turned homework in late. If I fail this—”

Pru spun around. Her teeth were clenched. “I’m not letting Maricela have her way. Not this time!” She dropped the shovel, then pushed open the door and stomped outside. Chica Linda mimicked Pru’s frustration by walking into her stall and turning her rump to everyone. Lucky was about to go after Pru but Abigail reached out.

“Let her be,” she said. “She’ll calm down.”

“Abigail, what’s the deal? Why do they hate each other so much?”

“They don’t exactly hate each other. It’s not that bad. It’s just that they both love to win. And there’s only one person in Miradero who beats Pru at stuff.”

“But Maricela doesn’t ride.”

“Not riding. Other things. Like, last year there was a competition to see which student would give the speech at the Founder’s Day parade. So we each had to write a speech, and the town council read them and they chose Maricela’s.”

“Was that because her dad is mayor?”

“Maybe,” Abigail said with a shrug. “Pru wrote about how this town was founded by people who came from many different places in the world like Mexico, Spain, Africa, and England, and that’s what makes Miradero such a special place. But Maricela’s speech was about how we should have fancier foods in the general store, like that weird duck stuff you put on crackers.”

“Foie gras,” Lucky said.

“Blech!” Abigail stuck out her tongue. Then she leaned against Boomerang. “Pru and I couldn’t figure out why the town council chose Maricela’s speech. But Pru never accused Maricela of cheating or anything.” Abigail lowered her voice to a whisper. “But I think maybe she cheated. Maybe her dad told the council they had to choose her speech or else.” She widened her eyes.

“Or else?”

“Yeah. You know, like…” Abigail cleared her throat, then mimicked the mayor’s loud voice. “If you don’t choose my daughter’s speech, I will force every member of this council to attend all of Maricela’s piano recitals, and all of her singing recitals.” She giggled.

That would be a terrible fate, but would the mayor do such a thing?

“There was also the time when Pru and Maricela tried out for the school play. Pru practiced her audition for weeks and she was really good. She has a pretty singing voice. Anyway, I went with Pru to the audition and somehow, when the piano started playing, Pru got off-key. Way off-key. Maricela ended up with the lead.”

“Do you think she got off-key because she was nervous?” Lucky asked.

“Maybe.” Abigail looked around, then leaned close to Lucky and spoke in a conspiratorial tone. “But maybe something else happened. The piano player is Maricela’s private teacher, so it’s possible she sabotaged the audition.” She shrugged. “But we have no proof, and I’m not one to spread rumors.”

Lucky was beginning to understand. Pru was a competitive person who always strove to do her best. She wasn’t a poor sport when it came to losing, as long as the losing was fair and square. But if Pru believed that Maricela had an unfair advantage, or had cheated in some way, then no wonder Pru was so frustrated.

This was a tricky situation. Of course Lucky wanted to support Pru and her feelings. But she also wanted to make things better at school and do a great job on this project. How could she fix this?

On Monday, she was supposed to walk to school with Maricela. That would give them time alone. Maricela seemed to want to be Lucky’s friend. Could Lucky convince her to change her mind about the group project?

Spirit nudged her from her thoughts. “Yes,” she told him. “Let’s go for a ride!”

13

Spirit’s eyes flew open. He turned his ears front, then back, trying to pinpoint the direction of the noise that had awoken him.

Earlier, he and his girl had taken a nice ride, and when they’d returned, he’d headed into the barn for a drink of water. He wandered into his stall, intending to take a brief nap. He’d wake long before twilight so he could get back to the herd.

But Spirit hadn’t realized that he was more tired than usual. It took more energy to ride in the cold air, and thus he’d slept longer than he’d intended.

What was that sound?

Chica Linda paced in the stall next to him, her ears flicking back and forth. Boomerang neighed in a high-pitched way. Somewhere, chickens were squawking. Something had agitated them.

Spirit pushed open his door and stepped outside.

Twilight had descended. The first stars were out, twinkling in the clear sky. The ground sparkled here and there with ice crystals. The chickens squawked again.

Spirit flared his nostrils. He knew that scent. Wolves!

He turned and ran toward the sounds, which had erupted into chaos. Squawking, screeching, cries of terror as the chickens tried to save their lives. He ran across the street, around a house, and into the backyard, where he skidded to a stop. Three pairs of yellow eyes turned and looked at him. The wolves had been circling the chicken coop, trying to dig beneath the fence. It was rare to see wolves this close to town. Wolves detested people and preferred the dense coverage of the forest. Only one thing would bring them here.

Hunger.

Spirit understood the wolves’ need for food, but his instinct was to protect. He reared on his hind legs, then brought his front legs down with a thud, purposely missing the nearest wolf by mere inches. A warning. The creature crouched. It pulled back its lips, fangs bared. Spirit reared again, landing even closer to the wolf and releasing a bugling neigh.

The wolves turned and ran.

From the corner of his eye, Spirit caught the glow of lanterns, followed by the sound of human voices. He watched the wolves retreating, their gray bodies disappearing into the night. They were headed away from town. Back to the forest. Back toward the river.

Back toward Spirit’s herd. Back toward the foals.

As the lanterns approached, Spirit broke into a gallop!

14

Maricela marched up the porch steps and knocked on the Prescotts’ front door. While waiting, she smoothed her green coat, then shook a leaf off her black boot. She’d brushed her hair one hundred times, as her mother had taught her, and she’d tied it back with a white ribbon, which contrasted nicely with her auburn waves. But then her mother had insisted on a wool hat, which had ruined the whole look. Stupid winter. How was anyone supposed to look stylish in all these layers?

Muffled steps sounded inside. Maricela shuffled in place, trying to stay warm. Her father had offered to take her to school in the wagon, where she could snuggle under a blanket, but she’d insisted on walking. She wanted this time, alone, with Lucky.

The door opened. “Hello, Maricela.” The smiling face belonged to Cora Prescott. Maricela smiled back.

“Hello, Miss Prescott. I’m here to collect Lucky. We’re walking to school.”

Cora seemed puzzled. Her eyes widened. “Really? Together?”

“Yes. Together.” Maricela didn’t appreciate Cora’s reaction. Why was this so surprising? As if they shouldn’t be friends, or as if it would be weird for them to be friends. Maricela and Lucky were from similar backgrounds, with similar upbringings. There was no one else in this backwoods town who was better suited to be Maricela’s friend. She just needed more time to persuade Lucky to accept this fact.

“Come in,” Cora said, waving Maricela inside. The house smelled like pancakes. A pot of coffee percolated on the potbelly stove. Cora walked to the bottom of the stairs and called, “Lucky!” Then she smiled again at Maricela. “I’m sure she’ll be down in a moment.”

“I certainly hope she doesn’t take too long,” Maricela said. “I’m supposed to deliver Lucky to school on time. Did you know that she

has the worst attendance record in school, on account of her tardiness?”

Cora pressed her fingertips together and looked directly into Maricela’s blue eyes. “While I appreciate honesty, Maricela, tattle-telling is not an admirable pastime for a young lady.” Then she began to clear breakfast dishes from the kitchen table.

Maricela glowered for a moment. Tattle-telling was something little kids did. She’d simply been providing information. Surely an aunt would want to know about her niece’s behavior so she could offer proper instruction. Maricela was about to argue this point when a loud stomping sound drew her attention. Lucky scrambled down the stairs. “I’m almost ready,” she announced as she shoved her arms into her coat. Her long brown hair clearly hadn’t been brushed one hundred times—maybe not even one time. Lucky darted past Maricela and grabbed her lunch bag off the counter. She planted a quick kiss on her aunt’s cheek. “Bye,” she said. Then she grabbed a pancake. “Want one?” she asked.

“No, thank you,” Maricela said. Though the pancake looked delicious, she wasn’t going to eat it with her fingers. Besides, she was wearing brand-new gloves.

“Suit yourself,” Lucky said with a shrug, then folded the pancake in half and ate it in two big bites.

“Hold on,” Cora said when Lucky was done chewing. “You’re not leaving with only a coat!” She wrapped a scarf around Lucky’s neck. “And this.” She set a hat on her head. “Oh, maybe another scarf?”

“Aunt Cora, I won’t be able to see or breathe if you keep putting layers on me.”

Cora laughed. “You’re right. I’m getting carried away.” She hugged her niece.

Lucky opened the door. Then she glanced over her shoulder at Maricela. “Come on or we’ll be late.”

“We will not be late. I’ve timed it perfectly,” Maricela said as she followed her outside.

“Have a nice day, you two,” Cora called before shutting the door.

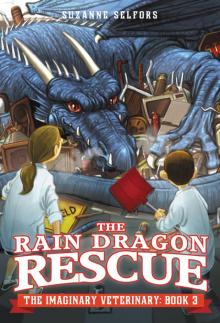

The Rain Dragon Rescue

The Rain Dragon Rescue Ginger Breadhouse and the Candy Fish Wish

Ginger Breadhouse and the Candy Fish Wish Ever After High: Lizzie Hearts and the Hedgehog’s Hexcellent Adventure: A Little Shuffle Story

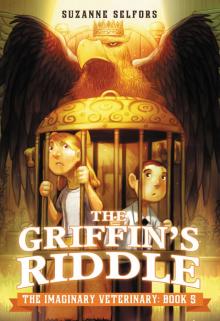

Ever After High: Lizzie Hearts and the Hedgehog’s Hexcellent Adventure: A Little Shuffle Story The Griffin's Riddle

The Griffin's Riddle Smells Like Pirates

Smells Like Pirates Duchess Swan and the Next Top Bird

Duchess Swan and the Next Top Bird The Sasquatch Escape

The Sasquatch Escape Hopper Croakington II and the Princely Present

Hopper Croakington II and the Princely Present The Order of the Unicorn

The Order of the Unicorn A Semi-Charming Kind of Life

A Semi-Charming Kind of Life Braver

Braver Kiss and Spell

Kiss and Spell Wedgie & Gizmo

Wedgie & Gizmo To Catch a Mermaid

To Catch a Mermaid Dexter Charming and the Trouble with Jackalopes

Dexter Charming and the Trouble with Jackalopes The Sweetest Spell

The Sweetest Spell CoffeeHouse Angel

CoffeeHouse Angel Wish Upon a Sleepover

Wish Upon a Sleepover Smells Like Dog

Smells Like Dog Ever After High

Ever After High Ever After High: A Semi-Charming Kind of Life

Ever After High: A Semi-Charming Kind of Life Saving Juliet

Saving Juliet Darling Charming and the Horse of a Different Color

Darling Charming and the Horse of a Different Color Wedgie & Gizmo vs. the Toof

Wedgie & Gizmo vs. the Toof Spirit Riding Free--The Adventure Begins

Spirit Riding Free--The Adventure Begins The Fairy Swarm

The Fairy Swarm Ever After High: Next Top Villain: A School Story

Ever After High: Next Top Villain: A School Story Fortune's Magic Farm

Fortune's Magic Farm The Lonely Lake Monster

The Lonely Lake Monster Spirit Riding Free--Lucky and the Mustangs of Miradero

Spirit Riding Free--Lucky and the Mustangs of Miradero Smells Like Treasure

Smells Like Treasure Mad Love

Mad Love